For more information or if you need help retrieving your data, please contact Weights & Biases Customer Support at support@wandb.com

LLM-as-a-judge refers to using large language models to evaluate the outputs of other AI systems by scoring responses for accuracy, relevance, safety, or any other user-specified criteria. These judge models leverage language understanding to make nuanced judgments about quality, much like a human evaluator would.

This approach has rapidly gained traction because it solves a fundamental problem in AI development: how do you evaluate systems at scale when human review is too slow and expensive and traditional metrics are too rigid? Consider the challenge of assessing a RAG system’s answers, or a chatbot’s helpfulness. Human evaluation provides gold-standard quality but does not scale beyond a few hundred examples. Rule-based metrics like BLEU or ROUGE capture surface patterns and miss semantic meaning entirely.

LLM-as-a-judge bridges this gap by delivering human-like judgments at machine speed and cost.

Its versatility extends across the entire AI development lifecycle. In evaluation, judge models assess whether answers are correct and whether they meet quality criteria like helpfulness and clarity, or violate anti-criteria like toxicity and hallucination. In training, judges generate preference pairs for RLHF (Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback) and GRPO (Group Relative Policy Optimization), rapidly labeling thousands of examples to accelerate model improvement. In production applications, judges monitor responses in real-time, acting as quality filters and guardrails that block unsafe outputs or trigger fallback behaviors when quality drops.

Research has demonstrated that LLM judges can achieve high agreement with human evaluators across diverse tasks, making them a practical tool for teams building and deploying AI systems at scale.

In this article, we’ll cover how LLM-as-a-judge systems work under the hood, their strengths and limitations backed by empirical research, research-validated best practices for building reliable judges, and practical frameworks like the RAG Triad for evaluating real-world applications. By the end you should know when to use LLM-as-a-judge and when to avoid it. Let’s dig in.

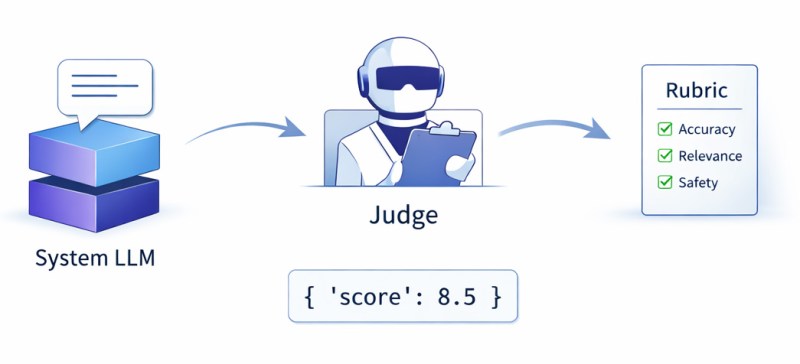

LLM-as-a-judge is a method where one AI model, known as the judge, evaluates the outputs of another AI model, called the system being judged. The judge provides scores, rankings, or feedback based on criteria such as relevance, accuracy, safety, or style. This approach automates or enhances manual quality control for a wide range of tasks, including chatbot conversations, code generation, and evaluation of answers from retrieval-augmented generation systems.

A typical setup involves three main components: the system generating responses, the judge model evaluating those responses, and a set of criteria or a rubric specifying what makes an output high or low quality. The judge receives the task description, the generated answer, and the evaluation rubric, returning structured feedback. This feedback can take several forms, such as a binary pass or fail, a numerical score, a ranking, or a detailed written explanation. Chain-of-thought reasoning can also be included, which makes the judge’s process transparent and easier to debug.

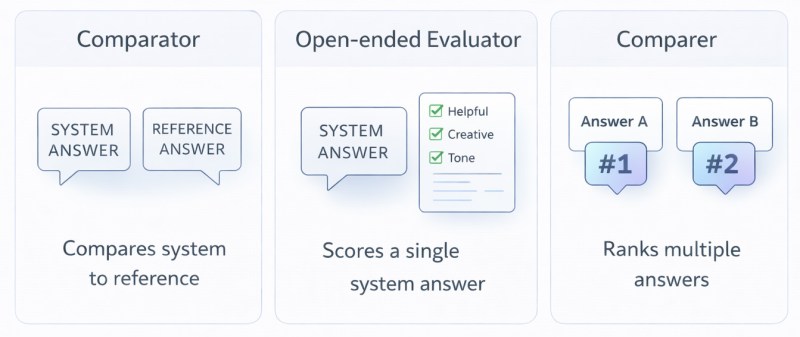

The three categories below represent a set of categories I have personally developed. Other groupings are possible, but this set provides the most practical and clear structure I have found for evaluation and monitoring:

The scope of LLM-as-a-judge evaluation is broad. Judges can be assigned to assess chatbot conversations, code snippets, summaries, translations, step-by-step reasoning, citation-backed answers, creative writing, or any case where quality matters. A judge may review a single response, compare multiple options, or score outputs against trusted reference answers.

One key advantage of this approach is flexibility. The same judge model can be used for dramatically different evaluation tasks by simply adjusting the prompt and the rubric. For example, evaluating medical accuracy relies on different criteria than judging the creativity of a story, but both can be addressed by the same judge with a suitable prompt.

LLM-as-a-judge also extends to process supervision using Process Reward Models, or PRMs. Rather than judging only the final answer, PRMs evaluate each step in a reasoning chain for logical coherence and correctness. This allows for catching where reasoning goes astray, not just whether the outcome is right or wrong. For multi-step problems, mathematical proofs, or complex planning, PRMs provide detailed feedback on each stage, helping to pinpoint both effective reasoning and specific mistakes. This kind of granular supervision enables more focused improvements than approaches that look only at final results.

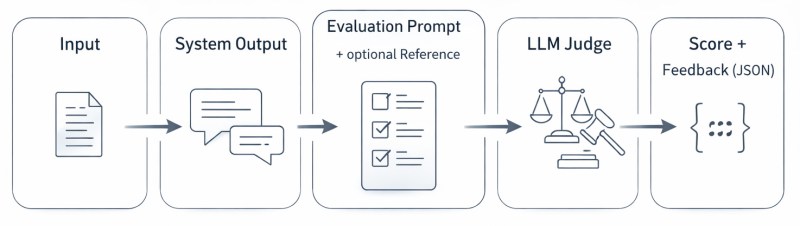

At its core, LLM-as-a-judge follows a straightforward pipeline:

input + system output (+ optional reference answer) → evaluation prompt → LLM judge → score

Understanding each step and the variations within this pipeline is crucial for building effective evaluation systems.

The process begins with collecting what needs to be evaluated. The input is the original query or task given to the system being judged, such as a user question, a prompt, or a problem statement. The system output is the response generated by the model under evaluation. Optionally, a reference answer (ground truth or gold standard response) can be included when evaluating factual accuracy or comparing against known correct answers.

These components are fed into an evaluation prompt sent to the judge LLM. This prompt is arguably the most critical piece of the entire system. It defines the judge’s role, specifies the evaluation criteria, provides the scoring scale, and sets output format requirements.

A well-crafted evaluation prompt might include:

After the judge responds, the evaluation system must parse the output. Structured output formats (JSON, XML) make this reliable and programmatic. A typical parsed result might include a numeric score, a categorical judgment (pass/fail, A/B/C grades), and reasoning explaining the decision. Parsing failures indicate prompt design issues and should trigger refinements to the evaluation prompt.

Single judges can be inconsistent or biased. Multi-judge ensembles address this by running multiple evaluations and aggregating results. Common strategies include:

These approaches increase reliability at the cost of more API calls and latency. The tradeoff depends on how critical accuracy is for the application.

Evaluating retrieval-augmented generation systems requires specialized metrics that go beyond general quality assessment.

The RAG Triad breaks evaluation into three components:

Alternative frameworks like RAGAS provide additional metrics, such as faithfulness (similar to groundedness), answer correctness (by comparing against reference answers), and context precision (ranking the quality of retrieved documents). These metrics can be evaluated by LLM judges with appropriately designed prompts that incorporate both the query and retrieved documents.

A reward model acts as a judge during preference-based training. In Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF), the process includes:

The reward model learns to mimic human preferences and serves as an automated judge to evaluate outputs at scale. This enables the model to receive consistent feedback and reinforces behaviors that match human values and criteria, making data collection and optimization much faster and more efficient.

Group Relative Policy Optimization (GRPO) takes a different approach by generating multiple candidate responses for each prompt and using relative rankings to guide training. LLM judges can rank these candidates, providing the preference signal needed for optimization without requiring explicit reward model training.

The key advantage is speed and scale: LLM judges can evaluate millions of examples for pennies per thousand, enabling rapid iteration on model training that would be prohibitively expensive with human labelers.

For tasks requiring multi-step reasoning, such as math problems, coding, or complex analysis, Process Reward Models evaluate intermediate steps rather than just final answers. PRMs assign scores to each reasoning step, identifying where the model’s logic breaks down.

LLM judges can serve as PRMs by evaluating each step of a chain-of-thought response:

This granular feedback enables training systems that not only produce correct final answers but follow sound reasoning throughout. It’s particularly valuable for catching subtle errors that lead to correct-looking but fundamentally flawed solutions.

PRMs can be trained discriminative models (smaller, faster, specialized for step verification) or LLM judges prompted to evaluate reasoning chains. The choice depends on throughput requirements, cost constraints, and the complexity of reasoning being evaluated.

The appeal of LLM-as-a-judge becomes clear when compared with the two traditional evaluation approaches: human review and automated metrics. Each method has distinct strengths and limitations, and understanding these tradeoffs determines when LLM judges provide the most value.

Human evaluation remains the gold standard for assessing open-ended AI outputs. Humans excel at nuanced judgment, such as recognizing subtle tone issues, detecting factual errors that require world knowledge, and applying complex multi-criteria tradeoffs that resist formal specification. When evaluating whether a chatbot response is helpful, appropriate, and well-tailored to context, human judgment captures dimensions that algorithms struggle with.

However, human evaluation has severe practical limitations. Cost scales linearly: evaluating 10,000 responses requires 10,000 human judgments, each taking minutes and costing dollars. A comprehensive evaluation of a production system generating millions of responses becomes prohibitively expensive.

Even with crowdsourcing platforms, collecting thousands of labels takes days or weeks, slowing iteration cycles. Additionally, human annotators often disagree, get fatigued, apply criteria differently over time, and introduce their own biases.

Studies of MT-Bench and Chatbot Arena demonstrate that strong LLM judges like GPT-4 achieve over 80% agreement with human preferences, matching the same level of agreement between different human evaluators. This isn’t perfect alignment, but it represents comparable inter-annotator reliability. The critical insight is that LLM judges approximate human-level judgment at a fraction of the cost and time.

Classic automated metrics like BLEU, ROUGE, METEOR, and F1 scores work well for tasks with objective correctness criteria and limited output variation. They excel at machine translation evaluation, extractive question answering, and classification tasks where responses are constrained.

These metrics rely heavily on n-gram matching and may not accurately capture the overall meaning or fluency of generated text. BLEU and ROUGE struggle with semantic equivalence. For example, if a generated answer rephrases content using different sentence structures or synonyms, these metrics may undervalue it despite correctness. A response can be perfectly accurate while sharing zero exact phrases with the reference, yet score poorly. Conversely, text with surface-level similarity but wrong context can score well.

BLEU has long been deemed inadequate for open-ended language generation, yet remains common due to lack of better alternatives. Traditional metrics provide no signal for tasks like “write a helpful email reply” or “explain this concept clearly” where quality exists on a spectrum across multiple dimensions and no single correct answer exists.

LLM judges represent a fundamentally different approach to defining evaluation metrics. Rather than mathematical formulas that compute surface statistics, they function as neural evaluation functions that follow instructions from a prompt. This shift enables evaluating semantic meaning and pragmatic quality rather than pattern matching.

LLM judges can assess whether an answer correctly addresses a question even when phrased completely differently from the reference, as well as judge tone, detect subtle logical errors, and apply complex multi-criteria rubrics.

LLM judges excel at evaluation tasks that require nuanced language understanding and subjective judgment. Traditional metrics struggle to capture criteria such as helpfulness, politeness, clarity, engagement, and appropriateness, dimensions that resist objective measurement but matter enormously for user experience. LLM judges can consistently apply these soft criteria at scale, providing reliable assessments where rule-based approaches fall short.

These capabilities extend to complex evaluation scenarios that demand deep language comprehension. Detecting bias, recognizing harmful content, assessing factual accuracy when world knowledge is required, and identifying subtle logical flaws all require understanding beyond surface-level pattern matching. LLM judges can reason about semantic meaning, contextual appropriateness, and logical consistency in ways that n-gram metrics cannot capture.

The flexibility of LLM judges makes them particularly valuable for domain-specific evaluation. The same judge model can assess medical Q&A, legal document analysis, code quality, creative writing, and customer support by simply adjusting the evaluation prompt, without requiring entirely different specialized metrics or expert human evaluators for each domain.

Beyond their language understanding capabilities, LLM judges offer practical operational benefits. Once the evaluation prompt is finalized, judges apply the same criteria identically across millions of examples, maintaining consistency that human evaluators struggle to match. Human annotators drift over time, get fatigued, and apply standards inconsistently, while LLM judges at fixed temperature remain stable. Evaluations are completed in seconds rather than minutes, making real-time guardrails in production feasible and enabling rapid iteration during development.

When judges provide chain-of-thought reasoning, they create audit trails that help developers understand failure modes, a level of explainability that human annotators rarely provide. The reproducibility of judge outputs supports rigorous experimentation, with the same prompt and model producing approximately the same results when re-run, enabling reliable A/B testing and regression detection across model versions.

LLM judges inherit the biases and limitations of their training data, creating systematic blind spots in evaluation. They exhibit position bias (preferring first or second responses regardless of quality), verbosity bias (favoring longer outputs), and self-enhancement bias (rating their own outputs higher). When humans disagree about evaluation criteria, judges inherit this ambiguity. These biases can be partially mitigated through careful prompt design, such as randomizing answer order, masking model identities, and explicitly penalizing length, or through fine-tuning judges on balanced datasets that correct for known biases, but they cannot be eliminated entirely.

Judge performance depends heavily on prompt design, making them brittle and sensitive to small changes. Minor adjustments to evaluation instructions can dramatically shift scores, requiring careful prompt engineering and validation. When judge models update or change versions, evaluation scores can shift even for identical content, complicating longitudinal comparisons and requiring re-baselining of benchmarks. This model drift creates challenges for teams tracking performance over time.

LLM judges can be fooled by adversarial examples and superficial optimizations. Systems that game evaluation metrics through formatting tricks, keyword stuffing, or verbose padding may score well despite poor actual quality. Judges may miss errors that fall outside their training distribution or fail to detect novel failure modes. High judge scores correlate with human preferences on average, but don’t guarantee users actually prefer the output in specific contexts, as judges can miss details that matter to real users.

Computational costs are cheap in comparison to human judgement, but are certainly not free. While cheaper than humans per evaluation, running millions of judge calls on large models adds up. For high-throughput production systems, cost and latency constraints may limit judge usage. More fundamentally, LLM judges lack accountability and should not make final decisions in high-stakes domains. Medical diagnosis, legal judgment, safety-critical systems, and content moderation with serious consequences require human oversight where errors cause harm. When correct answers are known and enumerable, such as math problems, factual queries with verifiable answers, or code that must pass tests, traditional metrics or rule-based checking is more reliable and cheaper than LLM judges.

Thanks to recent systematic research on LLM-as-a-Judge, notably work from CALM / “Justice or Prejudice?” (Ye et al.), we now have a well-characterized set of recurring biases that affect LLM judges across models and tasks. These biases are not edge cases; they are predictable failure modes that must be actively managed.

Presentation biases are among the most common. Judges exhibit position bias, preferring responses based on ordering, and verbosity bias, mistaking longer outputs for higher quality. These issues can be mitigated by randomizing answer order, evaluating multiple permutations, and explicitly penalizing redundancy or rewarding conciseness in the rubric.

Self-enhancement bias poses a special risk in automated training loops, as models tend to rate their own outputs higher than those from other systems. This can silently corrupt preference data and reward modeling. A strict separation between generation and evaluation models is essential, and self-evaluation should be avoided in production pipelines.

Beyond prompt design, system-level safeguards are critical. Multi-judge ensembles with score aggregation reduce idiosyncratic errors. Consistency checks, such as re-evaluating identical inputs, help detect instability. Logging all judge inputs, outputs, and scores enables drift monitoring when prompts or model versions change. Finally, periodic benchmarking against human judgments on a held-out set remains the only reliable way to validate that judge scores meaningfully reflect real quality.

Social-signal and process biases further distort judgments.

Authority and bandwagon biases cause judges to favor responses with citations, a confident tone, or claims of majority approval, even when those signals are irrelevant or fabricated.

Refinement-aware bias occurs when judges score an answer higher simply because they are told it was refined, overvaluing process metadata rather than the final content.

Sentiment and identity biases lead judges to react to emotional tone or demographic markers instead of substance. Mitigations include masking citations and popularity cues, evaluating answers in isolation without refinement history, neutralizing identity markers, and explicitly instructing judges to ignore tone and social context unless directly relevant.

LLM judges are powerful but imperfect measurement instruments. Treating them as fallible, validating them continuously, and stress-testing them against known biases is what turns LLM-as-a-Judge from a convenience into trustworthy evaluation infrastructure.

LLM-as-a-judge has become a practical default for evaluating open-ended AI systems. It enables scalable, human-like assessment in settings where traditional automated metrics fall short, but it also introduces meaningful tradeoffs around cost, latency, bias, and reliability. Understanding both its strengths and its limitations is essential for building robust evaluation pipelines.

LLM-as-a-judge makes large-scale evaluation of open-ended outputs feasible by approximating human judgment on criteria such as helpfulness, relevance, clarity, reasoning quality, and safety at a fraction of the cost and time required for human review. A single-judge model can be reused across tasks and domains by modifying only the evaluation prompt and rubric, thereby eliminating the need for task-specific metric engineering and enabling rapid experimentation.

Because judge outputs are returned quickly, LLM-as-a-judge fits naturally into regression testing, continuous evaluation, and CI-style workflows. It also enables preference-based training at scale by generating comparison data for methods such as RLHF, DPO, and GRPO without requiring large human labeling efforts. When used with fixed prompts and low temperature settings, LLM judges apply criteria consistently and avoid issues like annotator fatigue or day-to-day drift.

Despite the long list of Pros from the LLM-as-a-Judge, they provide an imperfect and noisy evaluation signal. While they often align with human preferences on average, individual judgments can be wrong, particularly on edge cases, long-tail inputs, or adversarial examples. Over time, models can learn to optimize for judge behavior rather than true quality, exploiting factors such as verbosity, formatting, or confident tone to achieve higher scores without meaningful improvement.

LLM-as-a-judge also introduces real operational cost and latency. Although significantly cheaper than human evaluation, judge calls are not free, and costs increase quickly at scale or when using strong models and long contexts. Using judges in latency-sensitive systems can complicate reliability guarantees and SLOs. In addition, LLM judges exhibit systematic biases and are sensitive to prompt wording, making scores brittle. For high-stakes domains such as medicine, law, or safety-critical systems, they should not be used as the sole evaluator.

For the combination of cost, flexibility, and qualitative performance, there is currently no true replacement for LLM-as-a-judge on open-ended tasks, but several complementary approaches are essential to mitigate its weaknesses. Standard metrics such as exact match, F1, BLEU, and ROUGE are advantageous since they are cheaper and faster than model-based judgment. Neural scorers, which are small or distilled models trained specifically to score or rank outputs, offer much lower cost and latency for high-throughput or near-real-time evaluation, but they trade flexibility for efficiency and typically require task-specific training data and added costs for the initial training and development of the model.

Human review remains necessary for high-stakes decisions, ambiguous cases, and for calibrating and validating automated evaluators. In practice, robust evaluation systems combine these methods, using LLM-as-a-judge as the primary qualitative signal while relying on objective metrics, deterministic checks, neural scorers for scale, and selective human oversight to ensure reliability.

LLM-as-a-judge is a useful evaluation primitive for real-world LLM systems where behavior depends on multiple components and cannot be fully captured by simple automated metrics. In production settings, models interact with retrieval systems, tools, policies, and user inputs, creating failure modes that are contextual, qualitative, and often ambiguous. LLM judges provide a scalable way to assess properties such as relevance, faithfulness, safety, and adherence to instructional guidelines across these complex pipelines.

For retrieval-augmented generation systems, LLM judges are commonly used to evaluate both intermediate and final outputs. Judges can assess whether retrieved documents are relevant to the user query, whether the generated answer is grounded in the retrieved context, and whether the response actually addresses the user’s intent. These signals help distinguish between retrieval failures, hallucinations during generation, and prompt or reasoning issues, and they are often tracked separately rather than collapsed into a single score.

LLM judges are commonly used to evaluate moderation and guardrail behavior in LLM systems. In this role, they assess whether model outputs comply with content and policy constraints, including toxicity, harassment, hate speech, self-harm, sexual content, refusal requirements, style guidelines, and sensitive information handling. Because they consider context and intent, LLM judges can handle borderline cases that are difficult for keyword filters or rigid rules.

These judges are typically used to audit safety behavior, analyze failure modes, and generate labeled data for training or calibrating moderation systems. In more complex setups, such as agentic or tool-using systems, they can also evaluate whether actions and tool use comply with policy, helping surface violations that are not visible from the final output alone.

In real-world deployments, judge-based evaluation is often used for offline analysis, regression testing, and monitoring. Judge scores and classifications are aggregated to track trends, compare system variants, and surface systematic regressions after changes to models, prompts, retrieval infrastructure, or safety rules. This approach provides visibility into system behavior without introducing additional latency or instability into user-facing paths.

LLM judges should not be treated as a single source of truth. For RAG systems, they work best alongside retrieval metrics, document coverage checks, and citation validation. For content moderation and guardrails, deterministic rules, allowlists, blocklists, and specialized classifiers remain essential. Selective human review is still required for high-impact decisions and for validating that judge behavior aligns with policy intent. When used as part of a layered evaluation strategy, LLM judges offer a practical and scalable way to reason about quality, safety, and compliance in real-world LLM systems.

A fundamental challenge for LLM judges is their tendency to rely on surface-level cues such as fluency, verbosity, or stylistic polish rather than genuine causal or logical understanding. Judges often favor longer, more detailed answers even when they contain flawed or spurious reasoning, and may fail to detect incorrect conclusions reached through invalid logic. Addressing this requires improving the fidelity of judge models’ reasoning. Moving beyond single-pass judgments toward structured reasoning pipelines where claims, evidence, and conclusions are evaluated separately can reduce the risk of rewarding outputs that merely sound correct, a concern that is especially critical for safety and guardrail evaluation.

Relying on a single LLM judge makes evaluation brittle and obscures genuine uncertainty. A single score often hides disagreement, ambiguity, or edge cases where the judgment is inherently unclear. Multi-model ensembles and disagreement analysis offer a promising direction. By using multiple judges and analyzing where and why they disagree, systems can better identify uncertain cases and trigger human review. Future aggregation methods may weight judges based on their strengths for specific dimensions, such as factuality, reasoning quality, or safety compliance, rather than treating all judges as equally reliable.

General-purpose LLMs often lack the domain knowledge needed to apply nuanced evaluation criteria in fields such as medicine, law, or software engineering. This mismatch leads to superficial evaluations that miss subtle but critical errors. A key future direction is the development of specialized judge models trained explicitly for evaluation rather than generation. Fine-tuning judges on high-quality, expert-annotated data can help them internalize domain-specific quality standards and recognize subtle failure modes.

LLM judges frequently express high confidence even when their judgments are unreliable, making it difficult for downstream systems to know when to trust or override them. This challenge is exacerbated by scalar scoring schemes that encourage false precision. Future work should focus on improved calibration and uncertainty quantification, enabling judges to produce confidence estimates, abstentions, or uncertainty-aware outputs.

While LLM judges are widely used to evaluate other models, the judges themselves are rarely subjected to rigorous, ongoing scrutiny. This creates blind spots around bias, stability, and failure modes. Developing robust meta-evaluation frameworks is an important future direction. Such frameworks should benchmark judge accuracy, measure agreement with human experts, detect systematic biases (including preferences for longer or more verbose answers), and track temporal drift as models and policies evolve.

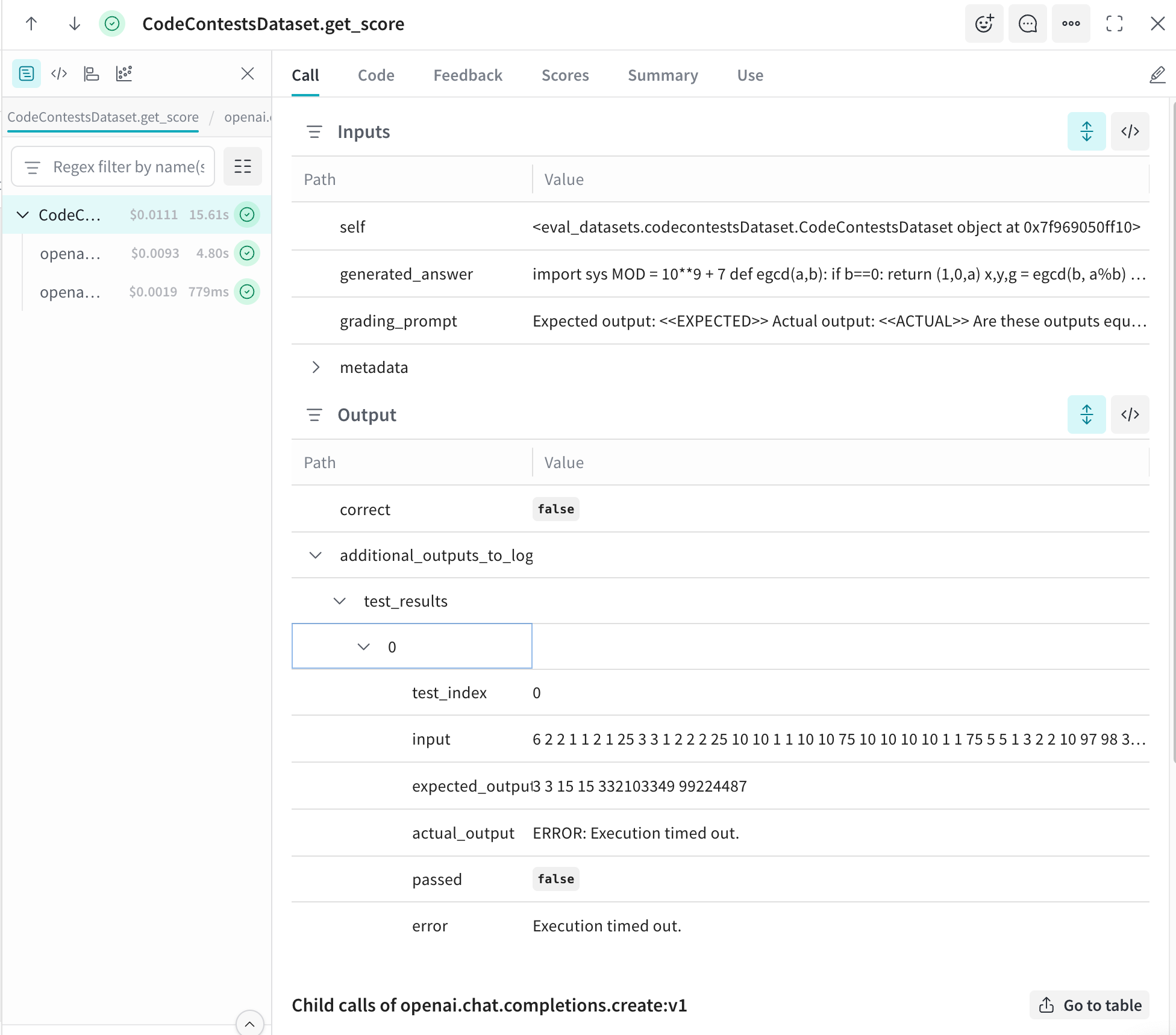

Another challenge is that LLM judges often rely on internal heuristics rather than verifiable evidence, especially when evaluating factual or technical correctness. Integrating external tools and knowledge, such as search engines, fact-checking databases, code execution environments, or domain-specific tools, can help judges ground their evaluations in external signals. Tool-augmented judges are less susceptible to hallucination and surface-level fluency bias, which enables more reliable verification of claims.

When LLM judges are used as guardrails or safety evaluators, they become targets for manipulation. Models can be optimized to satisfy the letter of evaluation criteria without achieving genuine safety or quality improvements. Future work on adversarial robustness is essential, particularly for guardrail applications. Judges must learn to detect superficial compliance, resist prompt-injection and formatting attacks, and evaluate deeper safety properties rather than easily gamed surface features. This includes assessing not just final outputs, but whether the underlying reasoning would remain valid under slight variations of the input.

LLM-as-a-judge has transitioned from a research technique into a core evaluation infrastructure for modern language model systems. It enables semantic, task-aware evaluation at a scale that human review and classical metrics cannot achieve, and it already plays a central role in training, benchmarking, and production monitoring.

The central lesson is that progress depends on making judge models more capable while deploying them responsibly. Many observed failure modes arise from limitations in reasoning fidelity. Addressing these limitations requires judges who can evaluate causal structure, detect flawed reasoning, verify claims against evidence, and express calibrated uncertainty scores.

The more powerful a judge model is, the more carefully the system needs to be designed. Since judges can affect how models are trained and what goes into production, their mistakes matter more. To use judges responsibly, teams should build processes that highlight uncertainty and bring in human reviewers when something is unclear or risky.

LLM-as-a-judge should be treated as an evolving measurement infrastructure. Like any measurement system, it requires continuous validation against human judgment, monitoring for drift as models and prompts change, and stress testing against known biases and adversarial behaviors. When improved in capability and integrated with complementary checks such as deterministic rules, external verification tools, and selective human oversight, LLM judges enable faster iteration, better training signals, and more transparent monitoring of real-world model behavior.

Used in this way, LLM-as-a-judge allows teams to reason systematically about quality, safety, and reasoning at a scale that would otherwise be impossible.